#greek coinage

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

owling. . .. jason molina .. central asian owl bad omen conceptions.. killing the owl gaining legitimacy .. but the owl is urself. .. the owl is a self sabotaging possessions.. positive owl symbolism .. the owl is very wise .. it can see a lot (blessing or curse?) .. the owl love lowkey killing you but it's good also? Let me yap ..#ITSOWLTIME

#owls!#owl#art#bird art#owl art#greek coinage#ancient greece#mughal art#jahangir#persian art#jason molina#songs ohia#magnolia electric co#album art#the mountain goats#tmg#miniature painting

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

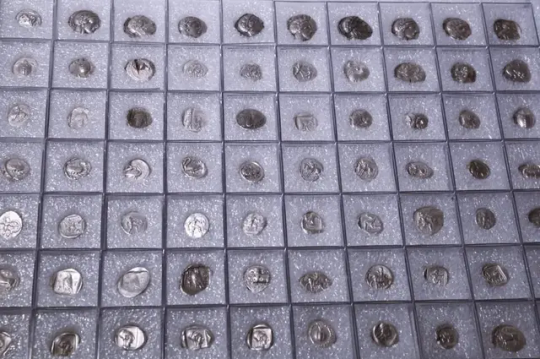

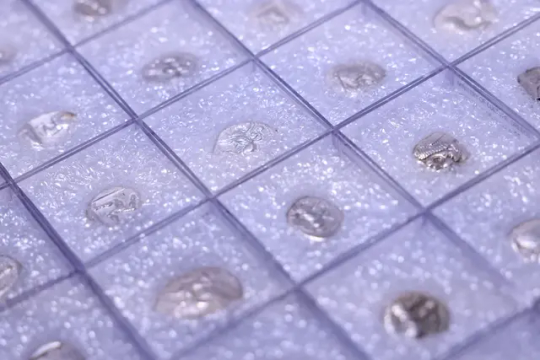

Greece Returns 1,055 Ancient Coins to Turkey

Greece on Thursday returned a hoard of over 1,000 stolen ancient coins to Turkey in the first repatriation of its kind between the historic rivals and neighbors, Agence France-Presse reported.

The move came a few months after Turkey publicly supported Greece in its long quest to reclaim the Parthenon Marbles from the British Museum in London.

Greek Culture Minister Lina Mendoni said the hoard of 1,055 silver coins had been seized by Greek customs guards on the border with Turkey in 2019.

“These coins had been illegally imported,” Mendoni said at a ceremony at the Numismatic Museum, which specializes in currency and medal collections, in Athens.

Greeks are “particularly sensitive” to repatriation issues, she said.

“All illegally exported antiquities from whichever country should return to their country of origin,” Mendoni added.

Turkish Culture Minister Mehmet Nuri Ersoy said the operation was the first repatriation from Greece.

Greek and Turkish experts determined that the coins were part of a stock hidden in Asia Minor between the late 5th and early 4th century BCE, she added.

While research is ongoing, it is possible the hoard was secreted in modern-day Turkey during the Persian Wars expeditions of Athenian general Cimon, a veteran of the 480 BCE Battle of Salamis, she added.

Broadly used

Most of the cache were tetradrachms — ancient large silver coins — originally minted in Athens and used broadly in the eastern Mediterranean, said Museum Numismatologist Vassiliki Stefanaki, a coinage expert.

Stamped with the image of an owl, the Athenian relics were also used locally to pay tribute to the Persian Empire, and Persian governors used them to reward their troops, she said.

Other coins came from Cyprus, the islands of Aegina and Milos, from Asia Minor cities founded by Greek settlers, the Iron Age kingdom of Lydia, and Phoenicia in modern-day Lebanon, officials said.

Mendoni on Thursday also thanked Turkey for supporting Greece’s campaign to secure the return of the Parthenon Marbles from London.

The British Museum has long maintained that the Marbles were removed from the Acropolis in Athens by royal decree granted to Lord Elgin, the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire.

But in June, Zeynep Boz, the head of the Turkish Culture Ministry’s anti-smuggling committee, told a UNESCO meeting in Paris that no such document had been found in Ottoman archives.

Her statement was “decisive” in favor of Greece’s position, Mendoni said Thursday.

Ersoy through a translator said Turkey wanted “with all its heart” to see the Marbles return to Athens.

“The Greek people should have them, they belong to them,” he said.

Boz, who attended Thursday’s ceremony in Athens, told Agence France-Presse that the timing of the coins’ return by Greece was not related to her report in June.

The five-year delay was caused by the time required by the Greek justice system to authorize the coins’ repatriation, she said.

#Greece Returns 1055 Ancient Coins to Turkey#silver#silver coins#ancient coins#ancient artifacts#tetradrachms#Persian Empire#archaeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#looted#stolen

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tetradrachm (Coin) Depicting the Goddess Athena

Greek, Athens, 490-322 BCE

The most famous of all civic badges was the profile of Athena, the tutelary goddess of Athens, stamped on the city’s coinage. While other cities modernized the looks of their coins, Athens retained this design, first used in about 520 BCE, to emphasize the dependability of its currency. With silver extracted from local mines, the city had a constant source of revenue for financing civic projects such as building a navy or rebuilding after the city was destroyed by the Persians in 480 BCE. The purity and stability of Athens’s coinage made it the standard throughout the Mediterranean for centuries.

207 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Invention of the First Coinage in Ancient Lydia

Money may take many forms, from the digital code of cryptocurrency to the woodpecker scalps favoured in early California. People have also used cattle, cacao beans, cowrie shells, chewing gum, grain, and giant stones as money. Early cultures became especially fond of metals, particularly silver, gold, and electrum (an alloy of the other two). These held their value (unlike a dead cow), were easy to transport (unlike a giant stone), and they could be measured out in exact amounts and fractions (unlike a woodpecker scalp). The only problem with metals is all the weighing. This adds time to every transaction, increasing the inconvenience and costs of doing business with bullion. There had to be a better way – and the ancient Lydians invented it.

Lydians Invent Coinage

In approximately 630 BCE, someone in the Anatolian kingdom of Lydia stamped a piece of precious metal with something akin to a signet ring. One outcome of this simple act was that it increased confidence in the lump’s weight and purity when later used in the marketplace. This procedure did nothing to modify the intrinsic value of the commodity, but it simplified the exchange of bullion for anyone willing to accept the stamp’s guarantee prima facie rather than reweighing and retesting the lump every time it was traded. Merchants could set aside their cumbersome scales, weights, and touchstones to accelerate their transactions by counting out, not weighing out, this new form of currency. The Greeks, who quickly adopted this Lydian technology, named the coins nomismata because they functioned as money by accepted convention (nomos).

That acceptance probably grew by degrees. The first time a fellow showed up in a Lydian marketplace with some stamped chunks of electrum, most of his neighbors may not have noticed or cared. The metal went into the balance pan with other bullion to pay a debt or purchase a lamb. Nothing differentiated the stamped and unstamped pieces until people could agree, by custom (nomos), that the message punched into the metal had special meaning. At that point, the object obtained the three essential elements of a coin as later stipulated by Isidore of Seville in the seventh century CE: acceptable metal, weight, and design. The stamps were rudimentary affairs at first, bearing messages in Greek or Lydian stating, "I am the signet of Phanes" or "I am of Kukas."

It must be remembered, however, that ancient peoples treated a seal more formally than we do a signature; the seal embodied the full power and prestige of the person associated with it. We might compare this to a document that has been notarized and not merely signed. These legends accompanied diverse images ranging from a lion to a stag, all hammered into the metal by a hardened die. Persons such as Phanes and Kukas (perhaps one a military commander and the other a king) stood surety for their stamped bullion in terms of its quality and quantity. Their prior involvement with the metal made it easier to transact business using it. To make this innovation even more convenient, coins were struck in seven denominations going down to a minute fraction (1/192) of a stater weighing less than a tenth of a gram (0.004 oz). This fact suggests a high degree of coin-based monetization, accommodating payments large and small across the Lydian economy.

Book Excerpt

Continue reading...

57 notes

·

View notes

Note

I would love to hear your opinions about ancient currency! And any recommendations you have for learning more about the Roman economy!

oh boy i am SO glad you asked! I'm going to put everything under a readmore because it's a Lot.

I have a few opinions on Greek coinage, specifically that of the introduction of coinage to Athens, though I'm working on a proposal for studying Spartan coinage rn.

Current publications re:Athens haven't really determined For Sure who introduced coins; it's a toss-up between Solon and Pisistratus but I'm in the Pisistratus camp for reasons that I can absolutely summarize in a separate post, as I've written and published a paper in my undergrad journal that (hopefully) holds weight in the current hodgepodge of thoughts. If you'd like that, I can write it up and link it here!

Re:Spartan coinage, I think the Spartan homoioi were real idiots. Most city-states were using silver (and very occasionally gold) for their coins, but Spartan homoioi were using iron spits. The spits (obeloi) were six to a drachma, which was the exchange rate for a long time. And by long time I mean there was no such thing as a floating conversion, coins were just the most portable form of precious metal, which was intrinsically valued. Outside Sparta (even the perioikoi) most city-states would have used ingots pre-coinage and that evolved into stamped metal, i.e. coinage. The Spartans considered themselves to be very religious and followed the Great Rhetra (unsure if Lykourgos existed), which maintained that silver and gold were holy and could not be used, so they used iron.

Unfortunately, the rest of Greece didn't follow that, and used silver in their coins, especially influenced by Attic-Ionian city-states who were in regular trade with Persia and further east, i.e. regions that valued precious metal outside their religious significance. Essentially, Spartans kinda screwed themselves over re:trade outside Sparta; they couldn't even trade in contemporary currency with the rest of Lakonia and forced their subject city-states into the same position. This is supported mostly by the explosion of Messenian and other Lakonian coinages after Sparta collapsed, though I want to see if I can find more text evidence, since I (an archaeologist) tend to rely too heavily on material. It's a whole thing, personally I believe this was a significant factor in Sparta's collapse, though other things factored in as well. Sparta was incredibly insular both in its trade/economy and religious practice and that combination led to its downfall.

For the Roman sources, I recommend starting with the Cambridge Companion to the Roman Economy by Walter Scheidel, and The Ancient Economy by Walter Scheidel and Sitta von Reden. Von Reden has excellent articles related to the ancient economy in general, and most are available on JSTOR, so I recommend giving her stuff a look.

I also highly recommend reading Moses Finley's work The Ancient Economy (no relation to Scheidel and Von Reden's work), as it lays the foundation for much of our current school of thought. Peter Temin's subsequent work, The Roman Market Economy argues against Finley and kicks off a whole debate about how to define an economy without using capitalism as the basis, because capitalism as we know and define it did not exist then, and it is incorrect to assume that. We can call it protocapitalist, but not capitalist.

Slavery in Rome is a nuanced subject that is integral to learning about its economy — I suggest keeping an open mind and treading carefully with respect to post-1492 slave trades. Noel Lenski's chapter "Framing the Question" (linked; you need access through your institution) discusses the slave trade against a Finleyan model, while Scheidel (him again) talks about how to determine the wages of slaves (JSTOR link). W. V. Harris talks about the demography and geography of slaves here (JSTOR link). These three are good starts for learning about Roman slavery, but if you want more sources, I can pull some up for you.

I don't want to overload you with sources, so in general I'll recommend anything by Scheidel, Von Reden, Nicholas Purcell and Peregrine Horden (connectivity), Seth Bernard (coins and emissions), Astrid Van Oyen (tech innovation), and Willem Jongman (economic structure). As with the slavery sources, if you want direct links I can definitely find them for you! I'm always happy to share info :)

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Symbols on ancient Greek coins

Ancient Greek coins often featured unique symbols or emblems that represented the city-state that minted them. These symbols were an early form of coinage emblem or "badge" that promoted the prestige of the city.

Some common symbols :

- Owls on Athenian coins, representing the city's patron goddess Athena.

- Pegasus on Corinthian coins, representing the mythological winged horse tamed by the hero Bellerophon.

- Bees on coins of Ephesus, representing the goddess Artemis who was associated with the city.

- Lions on coins of Miletus, a common symbol for the city.

- Roses on coins of Rhodes, representing the island's famous flower.

- Celery on coins of Selinunte, depicting the local plant.

These symbols were more than just decoration - they served to identify the issuing authority and promote the identity of the city-state. Coins were an important symbol of civic pride and power in the ancient Greek world. The variety of symbols used reflects the diversity of Greek city-states and their local mythologies and iconography. #archaeology #history #ancient #art #alsadeekalsadouk #ancienthistory #travel #archaeological #rome #italy #museum #roma #heritage #greek #arthistory #culture #antiquity

#4thcentury #photography #tetradrachm #greekcoin #greekarcheology #greekancientcoins #stater #الصديق_الصدوق

#Greek_mythology

#history#photography#greek coins#sidon saida tyre beirut phoenician الصديق_الصدوق#culture#travel#palestrina#archaeology

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been asked to weigh in.

So.

No, Cleopatra wasn't black. She wasn't even African. Her family was Macedonian Greek, and they were infamously the most incestuous family in Egyptian history. No African DNA got in there. People who saw her while she was alive described her as having, "honey skin." She wasn't Elizabeth Taylor white, but she also wasn't what we'd call black.

That being said, there are PLENTY of Black figures in Egypt. The further back you go in Egyptian history, the less amount of trade routes with other nations, the more African they were. That means that the pyramid builders like Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure were all likely black. Hatshepsut, the first woman to rule in her own right who established highly successful trade routes with Punt, was likely black. Tutankhamun's grandmother Tiye has always been depicted with dark skin. Queen Ahmose Nefertari was depicted as this:

Then there's the entire Kushite Dynasty from Sudan who were black. This was a non-issue for Egypt. The biggest issue was if you worshipped their gods and respected their ways. If you did, then you were in. Alexander the Great was received like a hero because of this while the Persians were hated because of their disrespect for Egyptian culture.

3. Egypt even had what historians considered to be Asian rulers. The Hyksos invaders who ruled Egypt were from West Asia and some historians have posited that they were from the Indian subcontinent. (This has not been confirmed.)

Egypt was a melting pot with people from all over because of the lucrative trade routes. They were ruled by Greeks, Romans, Persians, Assyrians, Kushites, Hyksos, Libyans, etc. They had a blended culture.

So, it is interesting to me that this documentary chose a woman who was very clearly documented to NOT be black when Egypt has no shortage of Black figures to choose from. You'd think you'd want to tie yourself to the great legacies like Hatshepsut who made Egypt wealthy and stable over Cleopatra who lost Egypt its independence.

4. The one thing I CAN say for certain is that the actual Egyptians were NOT white. When I hear conspiracy theories that Ramses II was white from Scotland because he had red hair, it makes me so angry. They were not. Great things can and did come for non-white nations. Writing, language, government, medicine, etc ALL came from non-white nations. Egyptians referred to the Celts as Barbarians for a reason. Cleopatra, while she ruled Egypt, was NOT Egyptian. And that always gets forgotten. She hailed from a conquerer's line, not Egypt itself.

The thing about Egypt was they realistically depicted skin-color in Egyptian art. Maybe one day we'll find something of Cleopatra that will put this to rest. All we know is that her coinage shows her with distinctive European features, like a long, narrow, hooked nose. She has her hair in the Greek style.

343 notes

·

View notes

Text

Powerful women from the classical world + excerpt of a letter from Lord Byron to Thomas Moore describing his lover Margarita Cogni (Venice, September 19th, 1818):

“I wish you a good night, with a Venetian benediction, ‘Benedetto te, e la terra che ti fara!’ — ‘May you be blessed, and the earth which you will make!’ — is it not pretty? You would think it still prettier if you had heard it, as I did two hours ago, from the lips of a Venetian girl, with large black eyes, a face like Faustina’s, and the figure of a Juno — tall and energetic as a Pythoness, with eyes flashing, and her dark hair streaming in the moonlight — one of those women who may be made any thing. I am sure if I put a poniard into the hand of this one, she would plunge it where I told her, — and into me, if I offended her. I like this kind of animal, and am sure that I should have preferred Medea to any woman that ever breathed.”

The mythical and historical allusions:

In Roman myth, Juno was Queen of the Gods as well as a military figure often depicted armed. In Greek myth, Medea was a sorceress who gets revenge against her unfaithful husband through murdering their children and his lover. Although “Pythoness” could refer to demonic witches in other uses, Byron is using it here as another name for Pythia or the Oracle of Delphi, a divine priestess and the most powerful female office in the ancient world.

Faustina is either a reference to the Younger or the Elder. Faustina the Younger was the wife of Marcus Aurelius; he revered her so much that he gave her enormous power, although later historians (probably falsely) accused her of being a murderer and adulteress. Faustina the Elder was the adoptive mother of Marcus Aurelius and was one of the most beloved Roman women in history, whose coinage often features Juno.

Byron's life and writing in context:

When he was living abroad in self-exile, Byron often sought to entertain his friends back home by sharing his adventures in lurid detail. His vivid letters became well-read throughout the 1800s, and are considered some of his best writing. Travel writing and adventure stories were extremely popular in the 19th century, and even most of Byron’s fiction champions these themes. Living abroad and traveling became marketable parts of Byron's celebrity. He blended his own experiences into his work, and chief among these were his romantic experiences.

Shelley once compared Byron to the Greek myth of Circe when writing in a letter about Byron's excessive amount of pets. Circe was known for seducing men and turning them into animals who roamed around her palace. Like a witch or an alchemist, Byron frequently transformed his lovers into characters through his writing. Like countless others, Margarita Cogni was mythically immortalized through the writer's description of her. She and Byron's other Venetian lovers have become part of the wider Romantic era mythology tradition, like the constantly retold tales of Mary Shelley's invention of Frankenstein, Percy Shelley's drowning, and John Keats' love for Fanny Brawne.

By using references to classical women in this letter Byron is not only paying tribute to mythology, history, and the Italian landscape in a way that his foreign audience would find tantalizing, but he is also exploring romanticized notions of classical female beauty which are at turns conventional and unconventional. He channels the gothic sublime through the otherworldly power and danger these women all represent, as well as channeling more traditional concepts of feminine strength rooted in modesty, beauty, and passivity. Byron creates poetic contradictions.

Just as he famously describes himself as “changeable, being everything by turns and nothing long,” he utilizes paradox and inconstance in his writing, such as in this satirical formulation of Margarita Cogni as the ideal lover who is both Goddess and woman, mistress and slave, contemporary and classical, masculine and feminine, wife and adulteress, murderess and murdered.

One can clearly see how this is the same chameolonic, binary-blurring poet who would go on to write the gender-bending themes of Don Juan — “If people contradict themselves, can I / Help contradicting them, and every body, / Even my veracious self?” — and who years beforehand had written She Walks in Beauty — where “all that’s best of dark and bright / Meet in her aspect and her eyes.”

#literature#english literature#lord byron#romanticism#poetry#dark academia#aesthetic#history#mythology#analysis#my analysis#my writing#my essays#byron#poems#letters#women#art#myth#greek#roman#british#english#academia#the romantics#love#romance

70 notes

·

View notes

Note

Politically, it always made sense that Alexander married the daughters of Darius III and Artaxerxes III. It even seems like a common move. But didn't the Greeks hold themselves to a higher standard than marrying a foreigner? Even if they didn't consider the Persians outright barbarians, they were foreigners and a conquered enemy. It seems also stranger that the marriage to Roxanna happened since she seems to be far from the ideal bride

What I am trying to ask is, didn't the Greeks expect Alexander to marry a Greek woman with a proper Greek wedding? I can grasp what Alexander had in mind with the Suda weddings, but it seems very strange that this “ethnic” “Greek” element is not present

ALEXANDER & MARRIAGE

(and what was Greek “ethnicity”)

First, let me link to 2 other posts that deal with Alexander and marriage, but don’t address the ethnic element except obliquely.

Argead Inheritance and Alexander’s (lack of) heirs

Why did it take so long for Alexander to father an heir?

A couple interpretive levels present here:

Greek ethnicity and marriage pre- and post-Persian wars

Macedonian expectations for (polygamous) royal marriage

Roman attitudes, especially Late Republic (Antony and Cleopatra in particular)

I want to note that Macedonians were regarded by Greeks—and regarded themselves—as a separate people. Today in Greece, The Macedonian Question is a hot-button issue that reflects MODERN politics and nationalism. We can now say (finally have enough epigraphical evidence) that the ancient Macedonians appear to have spoken a form of northern Doric Greek, distinct from Thessalian and Epirote forms, so by modern definitions, we’d consider them Greek.

But our ancient sources often speak of the Greeks and Macedonians as if they were different, if related, peoples. Certainly, while they shared many similarities, Macedonians were distinct, and didn’t especially want to BE Greeks. I tried to reflect that ancient attitude in Dancing with the Lion.

Furthermore, the tendency to glomp all of ancient Greece together reflects Early Modern ideas of nationhood. THERE WAS NO ANCIENT NATION CALLED GREECE. That’s one of the first things I teach in my “Intro to Greek History” class. 😊 “Greece” (Hellas)* was simply a landmass. In fact, the ancient Greeks don’t appear to have referred to themselves as “Greek”—an ethnicity—until the Persian invasion.** Ethnicities were “Athenian,” “Spartan,” “Corinthian,” “Theban,” etc. Independent city-states with their own laws, coinage, magistracies, etc. In addition, they recognized larger dialect groupings: Ionic-Attic, Doric, Aeolic, then subdivisions within that. These larger dialect groupings also shared social customs and dress, as well as distinct religious cult. So, for instance, you won’t find many/any temples to Hephaistus in Doric areas, and the peplos became associated with Doric women while Ionic-Attic wore the chiton. Even the later Roman province was called Achaia and didn’t include a lot of areas they’d have considered “Greek” (Hellene).

It took being invaded by a true “Other” (Persia) before they started to define themselves as Hellenes versus Barbaroi (not-Greeks)—yet they didn’t always agree on the “edges.” It’s not until late that we find Thessaly included at the Olympic games. Epiros was sorta-Greek, as they could claim Achilles, but both Epiros and Thessaly had semi-monarchic political systems not in line with accepted Greek norms (the polis). Macedon was even further afield, being a full-on monarchy. The Macedonian royal family claimed to be Greeks ruling over a non-Greek but cousin people; the (fictional) eponymous founder, Makedon, was a nephew of the equally fictional forefather of the Greeks: Hellen. The “Greekness” of the royal family was also a fiction, invented by Alexander I—in the wake of the Greco-Persians Wars, note.

Now, again, by modern criteria, we’d probably consider the Macedonians blended but largely Greek. Yet it’s important to recognize the difference between now and then—something I get frustrated over in modern arguments. (Which can be quite strident.)

Anyway, it’s during/after the Greco-Persian Wars that barbaros came to acquire a more negative connotation. In the Archaic Age, it was a neutral term. Barbaros simply meant “non-Greek speaker” or “the bar-bar people” (“those whose language sounds like bar-bar-bar-bar to us”). It’s not complimentary, but it’s also not as negative as it came to imply later.

Furthermore, in the Archaic Age, plenty of Greek men, including Athenians, married non-Greek women—often to cement business ties, especially in Asia Minor, Thrace, and Italy. In many city-states, these children were citizens if their father was. It’s only in a few city-states that both parents had to be citizens, such as Sparta and, later, Athens. These developments are either very late Archaic or Classical, in order to restrict citizen privileges.

IOW, even in Greece proper, marrying a Greek woman wasn’t important except in a few places, specifically to limit citizenship for economic reasons. Notions of ethnic purity as we understand it weren’t a thing. Yes, even in Sparta. Full Spartans excluded other Lakonians, who spoke the exact same language and kept the exact same religious cult. In short, all Spartiátēs were Lakedaimonians (the city-state) and Lakonians (ethnicity), but not all Lakonians and Lakedaimonians were Spartiátēs. E.g. Spartiátēs were the aristocratic class. (The alt-right really needs to figure that out … except, yeah, they don’t want to as it would mess with their biases.)

When Herodotos included “blood” in his famous definition of Greekness (to speak the Greek language, worship the Greek gods, keep Greek customs, have Greek blood—and to live in a polis), “blood” meant from DADDY. This relates a bit to ancient views that a mother was just a field to be plowed for male seed. Ergo, children inherited from their fathers. (This belief was not universal, especially later, but it informed early Greek thought, and thus, inheritance laws.)

NOW … Macedonia.

Macedonian kings practiced royal polygamy for political reasons. That means Alexander wasn’t the first to marry non-Macedonians. In fact, of Philip’s 7 wives, only Kleopatra (the last) is *distinguished* as a Macedonian. Even Phila is called Elimeian (Upper Macedonian) by Statyrus. Olympias was Epirote (Greek), Philina and Nikesepolis were Thessalian (Greek), Audata was Illyrian (non-Greek), and Meda was Getai Thracian (non-Greek).

Was there objection to Philip’s marrying the latter two? Our evidence doesn’t say. In the case of Audata, he may not have had a choice; marrying her was probably part of the peace deal with Bardyllis shortly after Philip came to the throne. Later, Meda was just “wife #6” so it’s unlikely anyone cared. Hooplah over Kleopatra as a “pure” Macedonian at their wedding was meant to diss Olympias, and thus, Alexander; it wasn’t a serious objection to Macedonian kings marrying non-Macedonian/Greek women. Especially as Epirote Olympias was Greek.

Things get even MORE complicated when we look at Alexander’s weddings. How much of the supposed objection to them is Macedonian, and how much from later Greek and Roman authors’ horror over “Orientals” generally? I’d submit Curtius’s bitching about Roxana is very ROMAN. Plutarch turns it all into a love affair, but has his own reasons for that. It’s really hard to know what to make of complaints. Was his taking of Persian brides itself offensive, or just as part of his overall adoption of Persian dress and customs? I’m sure there was no collective “Macedonian attitude” so much as various camps into which this or that solder fell—from strict Traditionalists like Kleitos through to Hephaistion, who is portrayed as supporting ATG’s Persianizing.

Last, I’ll also submit another reason we find anxiety about “foreign” wives in our Alexander histories: Octavian whipping up Roman nationalist fear of Cleopatra (VII) and Antony’s marriage to her. Cleopatra became a stand-in for the Wicked Wild Oriental East and corruption of Good Roman Virtues. She’s that “Egyptian woman” (yes, even though she was technically Greco-Macedonian). Caesar may have entertained an affair with her and nursed Alexander comparisons, but between Caesar and Octavian/Antony (in fact partly because of Caesar), Alexander imitatio had fallen out of favor and would stay so for a while in the early Republic.

Curtius would have been writing (we think; dating him is tricky) under the late Julio-Claudians. So yeah, them furrun’ wimmen gotta be watched out for! Marrying Roxane was part of Alexander’s seduction by the East after the death of Darius. That Roxane was not a princess (like Statiera) made it even worse. She was a TRUE barbarian.

Add to that, polygamy wasn’t understood by either Greek or Roman writers. Plutarch tries to explain Philip’s later marriage to Kleopatra as divorcing Olympias first (as does Justin) because Romans (and Greeks) used divorce. Polygamy was, to their minds, an eastern vice. So Alexander taking (unequivocably) three wives was oriental, proof of his corruption.

Hope this helps to contextualize what we’re looking at here, and the problems involved reading the sources.

If some Macedonians objected to Alexander marrying Roxane (and they probably did), it would have been because she wasn’t high-born enough for a (first) wife, and/or she was TOO foreign. But as that marriage got them out of Baktria/Sogdiana, it looked just like things Philip had done.

Later objections involved whether Roxane’s child should be accepted as heir over Arrhidaios. That’s a different kettle of fish. It’s clear that status of the mother was important in Macedonian inheritance squabbles even before Alexander. While some Macedonians preferred the mentally unfit Arrhidaios over the child of any “captive,” others did not. They wanted a son of Alexander.

So who he married mattered rather less than who was put forward to inherit the diadema.

---------------------------

* “Greek” is from the Latin Graecae, a specific Greek tribes, just like the Romans are a specific Latin tribe. The Romans just applied it to everybody on the peninsula. The Greeks called themselves “sons of Hellen”: Hellenes. The official name of the country even today is Hellas, not Greece. Hellen isn’t to be confused with the (feminine) Helen, btw. Hellen was a son of Deukalion, Helen the wife of Menelaus, and later mistress of Paris.

** For an excellent, if rather…er, thick discussion, with lots (and I mean LOTS) of ancient evidence, see Jonathan Hall’s Ethnic Identity in Greek Antiquity, which addresses the question of when the ancient Greeks became “Greeks.”

#asks#Alexander the Great#Greekness#ancient Greek ethnicity#Roxane#Barsine#ancient Macedonian ethnicity#Alexander's marriages#Philip's marriages#Macedonian polygamy#Alexander imatatio#Classics#Jonathan Hall#tagamemnon

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Various Greek coinage in all thier glory!

Larissa, Thessaly; Akragas, Sicily; Argos Peloponnese; Athens, Attica; Eretria, Euboea; Aegae, Macedonia; Ephesus, Ionia; Corinth, Peloponnese; Massalia.

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, anon here about Cleopatra. I didn't mean weird in general, I moved my US sentence in the wrong place. I wanted to say that for a movie happening in the US since the population is extremely heterogenous and in a city like California, New York. Most cities seem diverse, from what I've seen! But yeah, I wouldn't go to a German movie except half of them to be black and 1/3 to be Asian. I didn't mean it like that. Movies often are a reflection of their population after all.

I consume content from a lot of places! And I don't expect to see myself represented. I like to watch JP content for example, and I recently watched a Japanese movie and they were all Japanese and it felt absolutely normal. In Kdramas most people are Korean too.

I watched an anime called Vinland Saga made by Japanese people. And while Anime is very stylized in terms of features, the designs imho showed that they were from another culture. Just wanted to clear that up hehe ~~~~~

So when I said it's a US centric thing, I just feel like a lot of Americans just except the same heterogeneity in other cultures as well and it doesnt sit right with them. But I simply don't get it. I don't get why changing someone's skin color immediately make them so relatable. Why they can't just keep Cleopatra with features more similar to the information we got (coinage, origin, etc)?

I often see the argument color doesn't matter, they can change it (i dont agree especially for historical figures) and they are trying to be more diverse so people could relate to them. But I don't get it. If color doesn't matter, why change it anyway? And why would I need to see a Black Cleopatra with Afro to feel good about myself? And if it's so important why just not tell the stories of people from my culture?

It's getting long but I'm almost done hehe

I've had the same issue with Achilles being black and the arguments justifying it. Like I've read that whole Homer describes Achilles with blonde hair it is a rough translation. And that Greek colors terms are quite strange and don't map out well with ours, etc. Anf that a god is a god and could take any form.

Well, I don't know if I'm alone in this but I don't get the mental gymnastics.

I like your takes btw!!! Sorry for elaborating sm in another message. And I'm a bit shy ig that's why I stay anon. Bye!!

My dear Anon there is no need to panic and write so much I am not accusing anyone I am elaborating. Either way yes I agree. To use an area like a multi-cultural neighborhood in the US and immediately assume that all films regardless of their setting, time or place need to reflect that is just wrong, as you brilliantly said and yes I also believe it is more a US-centered idea (which though seems to spread in other parts of the world as well) and that happens because most high-grossing films and series are US produced. But even UK Productions seem to be trying to fit this recently, at least to my knowledge but yeah it is still, I believe a more US-centered idea.

The funny part is that they hurt their own narrative. Because right now the viewers are so tired of it that once they see diverse cast they don't always feel eager to see it out of fear that the diversity is just made up. And this is sad because genuinely good films are not given the attention they deserve. Or actors that are probably marvelous and do very good job, are doomed to be compared with the actual characters they ellegedly represent and not in a good way so many talented individuals also get dragged down for no reason

Oh yeah I really genuinely loooove it when people bring out excuses such as "there is no clear description of the character" as an excuse and again instead of making them then as what the ethnicity might as well have looked like they just add random stuff and oftentimes as you brilliantly say they do not care; Achilles was described having long, blonde hair (and yeah although the word "xanthos" aka "blonde" in general can be translated in various colors starting from blonde to auburn to light brown still what they gave us makes no sense). Not only did they randomly race-swappped Achilles they also casted a guy that had his hair shaven! Like they didn't even do the courtesy to add the long hair Achilles had in the Iliad (which WAS described and was of outmost importance too given how it was offered to the pyre of Patroclus)

I agree with you Anon. This mental gymnastics is so tiring especially since as I said are so terribly one-sided. Color doesn't matter when it comes to stories set in Europe but it is somehow of vital importance for Africa or Asia; accurate representation doesn't matter for Greek mythology because "they are just entertainment" while somehow it is a matter of life and death when depicting mythologies from other parts of the world because "we must be respectful"

So indeed which is it? And by the way I am with both sides here. OBVIOUSLY I don't want African or Indian or other traditions be swapped with anything. I want to see genuine transfers of myths and legends on big screen or on cartoons etc because all legends deserve it! Greek mythology included. Because myths are representatives of culture and history for every nation and ethnos.

Thank you so much for your takes Anon and yes I understand. Many people feel shy or worried epsecially on the internet and prefer anonymity.

#katerinaaqu answers#more on representing cultures in media#all cultures deserve their appropriate attention in media

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Berlin Cleopatra, a Roman sculpture of Cleopatra wearing a royal diadem, mid-1st century BC, now in the Altes Museum, Germany

—

The Enigma of Cleopatra: Modern Reconstructions and the Quest for Her True Appearance

If one thing is clear from various accounts and reconstructions of Cleopatra, it's that her allure went far beyond her physical appearance.

Cleopatra VII (70/69 BC – 10 August 30 BC), the last queen of Egypt, has been a character of fascination and intrigue for centuries.

Known for her intelligence, charm and political acumen, she was a woman who made a significant mark in a world dominated by men.

She was fluent in multiple languages, well-versed in politics, and an astute diplomat — traits that made her a formidable leader.

However, the question of her physical appearance, specifically her beauty, has always been a topic of debate.

Her true power lay in her intellect, her charm, and her political acumen.

Cleopatra’s ability to captivate and influence others was central to her rule.

She managed to form alliances with two of the most powerful Romans of the time — Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, which were crucial for the maintenance of her power in Egypt.

These alliances and the relationships she forged speak volumes about her charisma and ability to persuade.

One of most enduring portrayals of Cleopatra is that of a woman of unparalleled beauty.

This is a narrative that has been perpetuated by countless plays, movies and novels, most notably William Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra.

However, the historical texts present a somewhat different picture.

Plutarch (c. AD 46 – after AD 119), a Greek biographer and essayist, made the earliest surviving description of Cleopatra in his work "Parallel Lives."

Interestingly, he doesn't dwell on her physical appearance but emphasizes her charismatic persona and intellectual prowess.

He notes that "her actual beauty, it is said, was not in itself so remarkable, but the attraction of her person and the character that attended all she said or did were something bewitching."

Cassius Dio (c. 165 – c. 23), another Roman historian, also focused more on Cleopatra's persuasive abilities and personal charm than her physical attractiveness.

These descriptions suggest that Cleopatra’s allure was not based solely, or even primarily, on her looks.

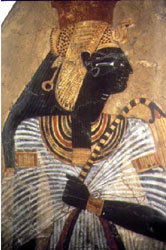

In contrast to the romanticized portrayals of Cleopatra, the extant artistic depictions and coinage of her profile provide a more realistic, albeit stylized, representation of her appearance.

Coins minted during Cleopatra's reign depict her with a prominent nose, a strong chin, and deep-set eyes.

Some historians believe that these coins were a deliberate political statement, indicating Cleopatra's desire to be seen as equal to her male counterparts.

Similarly, the few surviving statues and carvings of Cleopatra from the ancient world do not present an image of classical beauty.

The Berlin Cleopatra, a painted limestone statue from 1st century BC, shows her with a hooked nose and a stern expression.

© The Archaeologist

#Cleopatra#Berlin Cleopatra#Cleopatra VII#egyptian queen#ancient egypt#classical beauty#intelligence#charm#political acumen#Julius Caesar#Mark Antony#ancient rome#roman empire#egypt#Antony and Cleopatra#William Shakespeare#Plutarch#Cassius Dio#coins#Altes Museum#Germany

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

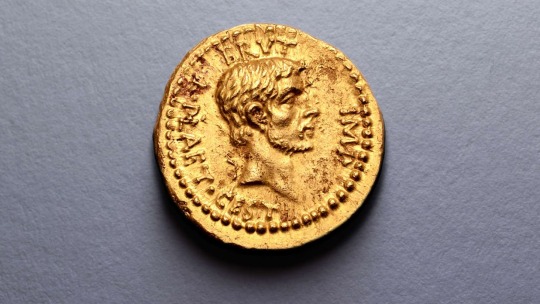

Very Rare Roman Gold Coin is Returned to Greece

A Very Rare Gold Coin, Minted by Brutus to Mark Caesar’s Death, Is Returned to Greece

The gold coin, which dates from 42 B.C. and is valued at $4.2 million, is thought to have been looted from a field near where an army loyal to Brutus camped during the struggle for control of Rome.

A rare and ancient gold coin that morbidly celebrates the stabbing death of Julius Caesar was returned this week to Greek officials by investigators in New York who had determined it was looted and fraudulently put up for sale at auction in 2020.

The coin, known as the “Eid Mar” and valued at $4.2 million, features the face of Marcus Junius Brutus, the onetime friend and ally of Caesar who, along with other Roman senators, murdered him on the Ides of March in 44 B.C. According to historians and experts, Brutus had the coins minted in gold and silver to applaud Caesar’s downfall and to pay his soldiers during the civil war that followed the killing.

The return Tuesday came at a ceremony attended by officials of the Manhattan district attorney’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit and U.S. Homeland Security Investigations, who cooperated on the case.

The coin, one of 29 artifacts returned to Greek officials, was given up earlier this year by an unidentified American billionaire who, investigators said, had bought it in good faith in 2020. The British dealer who helped to arrange the sale was arrested in January, and the coin itself was recovered in February, officials said.

Experts said the coin, minted two years after Caesar’s death, is about the size of a nickel and weighs about 8 grams, and is one of only three known to be in circulation. A silver version of the coin was also minted and about 100 are known to exist. Those can sell for $200,000 to $400,000.

“The Eid Mar is an undisputed masterpiece of ancient coinage,” Mark Salzberg, the chairman of Numismatic Guaranty Corp., which verified the coin but does not research provenances, said in a statement in 2020.

Experts said they believe the coin was likely discovered more than a decade ago in an area of current-day Greece where Brutus and his civil war ally, Gaius Cassius Longinus, were encamped with their army.

The front, or obverse, of the coin features an engraved side view of Brutus and the Latin letters “BRVT IMP” and “L PLAET CEST.” Experts say the former stands for “Brutus, Imperator,” with imperator referring not to emperor but to commander. The latter stands for Lucius Plaetorius Cestianus, who was a treasurer of sorts for Brutus and oversaw the minting and assaying of his coins.

The reverse features two daggers on either side of a cap known as a pileus. The daggers stand for Brutus and Cassius and reflect the manner of Caesar’s death, experts say, while the cap is a symbol of liberty that was worn by freed slaves. Overall, the image is meant to celebrate the murder as an act by which Rome was liberated from Caesar’s tyranny. Beneath the symbols is the Latin inscription “EID MAR,” designating the Ides of March — March 15, 44 B.C. — the fateful day on which the conspirators left Caesar dead on the floor of the Roman Senate.

Historians see irony in the fact that Brutus, who had admonished Caesar before the murder for the self-aggrandizing act of putting his face on Roman coinage, wound up doing the same with his own coins.

Ultimately, the forces who favored the dead Caesar, led by Mark Antony and others, defeated Brutus and his men in October of 42 B.C. at the Second Battle of Philippi, and Brutus and Cassius committed suicide.

According to investigators, the coin is first thought to have come to market between 2013 and 2014. Richard Beale, 38, director of the London-based auction house Roma Numismatics, put it up for sale on his company’s website and over several years shopped it at coin shows in the United States and Europe before it was sold in October 2020. The $4.2 million was the most ever paid for an ancient coin, according to the Numismatic Guaranty Corp.

Mr. Beale is charged with grand larceny in the first degree and several other felonies and was released on his own recognizance. His lawyer, Henry E. Mazurek, declined to comment on the case.

Among the other Greek antiquities repatriated on Tuesday were figurines of people and animals; marble, silver, bronze and clay vessels; and gold and bronze jewelry. Their total value was put at $20 million.

In remarks at the ceremony, Konstantinos Konstantinou, Greece’s consul general in New York, said his country has been hit hard by the illicit trading of antiquities and is seeking their return “in every possible way.”

He praised investigators for “striking down the illegal international criminal networks whose activity distorts the identity of peoples, as it cuts off archaeological finds from their context and transforms them from evidence of people’s history into mere works of art.”

By Tom Mashberg.

#Very Rare Roman Gold Coin is Returned to Greece#Julius Caesar#Marcus Junius Brutus#Eid Mar#gold#gold coin#collectable coin#ancient artifacts#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire#Mark Antony#Second Battle of Philippi#long reads

213 notes

·

View notes

Note

How exactly did Hercules become connected to Vajrapani to being the protector of Buddha? And what’s his relationship of the Nio in Japan?

Katsumi Tanabe notes here that despite the widespread acceptance of the view Heracles influenced the early iconography of Vajrapani in Gandhara, there’s actually no consensus on how this phenomenon originally developed. Full explanation under the cut.

For context: Greek iconographic types were commonly adopted in Central Asia - typically for Iranian deities (who especially in the east were closer to deities in the strict sense than to the Zoroastrian notion of yazatas). However, the logic of these associations was not necessarily as simple as interpretatio graeca resulting in adoption of iconography. Nothing illustrates this point better than the fact Bactrians regarded Oxus as the king of the gods, but adopted the iconography of Marsyas for him, probably because it was a relatively widespread Greek image of a river god as opposed to some deeper analogy between their respective characters. There are also cases where iconography differs from what interpretatio would suggest - Tishtrya was seemingly associated with Apollo, but iconographically took after Artemis instead on Kushan coinage. Therefore, each case needs to be approached separately.

A particularly remarkable example of Heracles-like Vajrapani (British Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

I don’t think there’s any need to undermine the transmission of iconography itself: it’s not hard to find representations of Vajrapani from Gandhara which basically look like Heracles holding a vajra (and sometimes a sword or a fly whisk) instead of a mace. However, it's worth pointing out he's actually not depicted entirely consistently in Gandharan art. In addition to the numerous Heracles-like examples, there are also cases where he resembles Silenus or another satyr; Zeus (a fairly natural match given his typical thunderbolt attribute and Varjapani’s… well, varja); Hermes; Dionysus; Alexander the Great; or an ordinary Kushan in period-appropriate clothing. Interestingly despite Varjapani being considered a yaksha, no images of him actually resemble the conventional depictions of yakshas from further south, which at the time typically drew from Indian royal iconography. Interestingly it seems only two other Buddhist figures were patterned on Greek ones in Gandharan art, Panchika (for unknown reasons depicted in the form of Hermes) and Hariti (who borrowed Tyche’s cornucopia though this was not a consistent attribute).

Ladislav Stančo in his monograph Greek gods in the East: Hellenistic Iconographic Schemes in Central Asia present a rather bold theory: the adoption of Heracles-like iconography for Varjapani was less a case of syncretism and more the result of artists familiar with Hellenistic standards being hired by Buddhists and repurposing standard forms their were familiar with already. They would often be operating only on vague descriptions of Buddhist figures they heard from the commissioners. With time these would become a standard in their own right.

However, there are other theories too - I’ll simply summarize here what Karl Galinsky wrote in his article Herakles Vajrapani, the Companion of Buddha from the recent Herakles Inside and Outside the Church: From the first Apologists to the end of the Quattrocento.

Obviously, the fact both figures are characterized by their strength is a commonly cited factor. Another possibility is that Varjapani might have absorbed Heracles’ iconography after Kushan kings started promoting Buddhism because of a shared association with royalty. Yet another option is that Varjapani was a traveling companion of the Buddha which made him a good match for globetrotting Heracles. Finally, the fact they could both fulfill many distinct roles could be an argument in favor of identification in its own right (Galinsky seems to support this proposal himself).

In the past arguments have been made that Heracles’ iconography survived in Central Asia through Vajrapani as late as in the sixth and seventh centuries (source; note the article still follows the vintage theory Vajrapani was in part a Buddhist adoption of Zoroastrian fravashi, which I haven’t seen validated in anything recent), based on a mural showing a figure wearing a lion skin from the Kizil Caves. There is a recent article which tries to salvage this point, but the author admits this is all highly speculative. In any case, by the time Varjapani reached China his attire started to change, and he came to be shown either with a bare chest or in armor, but no longer nearly naked like Heracles. He also commonly has the exaggerated facial features you’d expect from yakshas and other similar beings, as seen for example on a mural from the Mogao Caves:

(wikimedia commons)

Vajrapani appears in later Buddhist tradition in an assortment of tales which typically portray him subduing demons or unruly deities on behalf of the Buddha. None of them really show much Greek influence, though - I don’t really think Heracles is known for fighting Maheshvara, and in turn Vajrapani never got to free Prometheus or complete any of the twelve labors (though we know the myths themselves were known in Central Asia); iconography and mythology could be transmitted independently of each other.

A Japanese depiction of Varhapani - note the third eye (Art Institute Chicago; reproduced here for educational purposes only) In Japan, Varjapani (Kongōshu, 金剛手; Shukongōshin, 執金剛神; Kongō-rikishi, 金剛力士 etc.) only appeared after a long process of transformations in Mahayana tradition, and his depictions generally reflect Chinese artistic conventions. The Niō, literally “benevolent kings”, are a double manifestation of him and similarly reflect a Chinese model. I don’t think there’s any real reason to claim there’s all that much Heracles in them. JAANUS notes that multiple identities could be assigned to them, though none particularly consistently. There’s a case to be made that the fact they are most commonly statues guarding temple gates is basically the core of their character judging from the proliferation of legends which revolve around this (for a Chinese example see here, Japanese ones are mentioned briefly in the linked JAANUS entries). They also only became widespread in the Kamakura period, centuries after even the boldest theories suggest the survival of some memory of Heracles in Buddhist sources. To put it differently: both Heracles and Nio are undeniably parts of Varjapani's history, but they are not necessarily a part of each other's history just because of that.

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Roman Baths

Roman Baths were designed for bathing and relaxing and were a common feature of cities throughout the Roman empire. Baths included a wide diversity of rooms with different temperatures, as well as swimming pools and places to read, relax, and socialise. Roman baths, with their large covered spaces, were important drivers in architectural innovation, notably in the use of domes.

A Mainstay of Roman Culture

Public baths were a feature of ancient Greek towns but were usually limited to a series of hip-baths. The Romans expanded the idea to incorporate a wide array of facilities and baths became common in even the smaller towns of the Roman world, where they were often located near the forum. In addition to public baths, wealthy citizens often had their own private baths constructed as a part of their villa and baths were even constructed for the legions of the Roman army when on campaign. However, it was in the large cities that these bath complexes (balnea or thermae) took on monumental proportions with vast colonnades and wide-spanning arches and domes. Baths were built using millions of fireproof terracotta bricks and the finished buildings were usually sumptuous affairs with fine mosaic floors, marble-covered walls, and decorative statues.

Generally opening around lunchtime and open until dusk, baths were accessible to all, both rich and poor. In the reign of Diocletian, for example, the entrance fee was a mere two denarii - the smallest denomination of bronze coinage. Sometimes, on occasions such as public holidays, the baths were even free to enter.

Continue reading...

125 notes

·

View notes